Introduction

Robyn Joy Park

Rebecca Kimmel

Dee Iraca & Becca Webster

Yooree Kim

More Stories

They’re among what’s thought to be the world’s largest diaspora of adoptees. As these Korean adoptees search for their roots, some are finding what they knew about their past isn’t true.

to hear sound in this story

I was adopted to Sweden [in] 1974

I was adopted to Denmark in 1972

I was adopted to the United States in 1978

I was adopted into France in 1982

“Who Am I, Then?”

Falsified Records. Swapped Identities. Stories from South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning.

It’s impossible to know how many of the estimated 200,000 adoptions out of South Korea were handled improperly. But according to reporting by The Associated Press and FRONTLINE, some adoptees looking into their origins have found erased histories, mistaken reunions, falsified adoption papers and switched identities.

South Korea’s transnational adoption system evolved out of the devastation of the Korean War in the 1950s. To the South Korean government, foreign adoptions became a way to reduce social welfare spending and export children it saw as socially undesirable — whether that was biracial babies, children of unmarried mothers or those born to poor families needing support.

As demand for South Korean children started pouring in from the West, critics say adoption agencies competed to rapidly send children abroad in the 1970s and ‘80s and sometimes tampered with paperwork to make more children qualify for adoption.

Records from the early ‘80s show that Korean government officials were aware that adoption agencies were aggressively competing for children and profit, but largely ignored those problems while pushing agencies to “facilitate as many adoptions as possible.” But by the end of the 1980s — when South Korea was transitioning from a military dictatorship to a democracy and it prepared to host the 1988 Olympics — uncomfortable questions were beginning to be raised about the country’s adoption system. The government began clamping down on how agencies operated, and adoptions began to plummet.

Now, hundreds of adoptees have submitted their cases to South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate whether their adoptions were mishandled. Some Western countries have changed international adoption rules or stopped it altogether, and the U.S. State Department has said it will review past practices.

South Korean adoption agencies have declined to comment on specific adoption cases. Throughout the years, the agencies have denied systemic wrongdoing and publicly pointed to the benefits of adoption as a way of saving vulnerable children.

These are the stories of adoptees out of South Korea who are now demanding answers from a system that critics say went from finding families for children to finding children for families.

[It] really flipped my world upside down and had me really questioning … who am I, then?

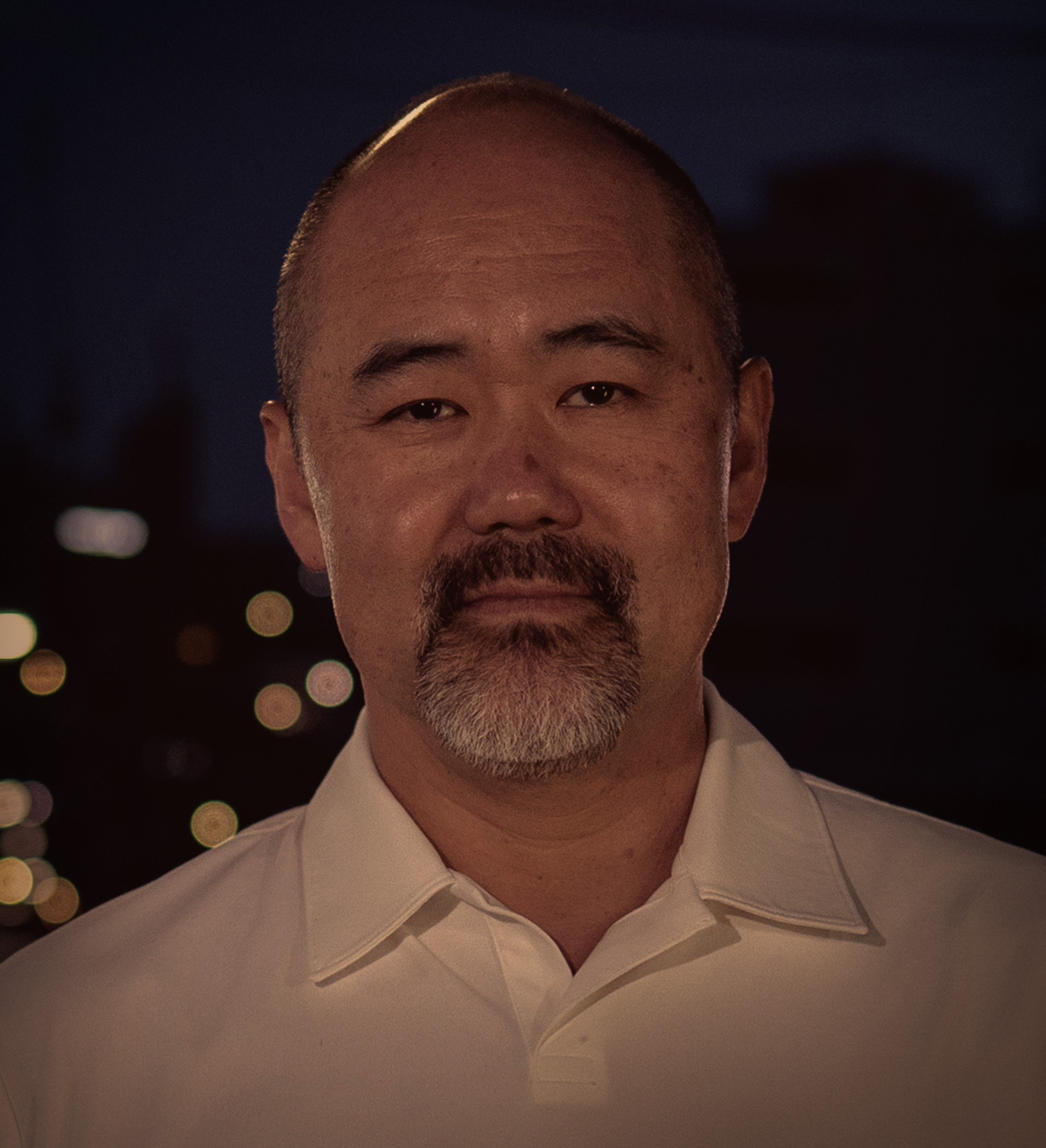

Robyn Joy Park

Adopted in 1982 to the United States

Robyn Joy Park, who was adopted by parents in Minnesota in 1982, says she had a desire to meet her biological mother from “day one.” Her adoption papers describe her as a girl named Park Joo Young, born in the city of Busan, and relinquished to an adoption agency by an unwed mother who worried about the challenges of raising her child alone.

In 2007, Park traveled to South Korea to meet a woman whom the adoption agency, Eastern Social Welfare Society, said was her biological mother. She and Park developed a deep bond over several years. They visited relatives, shared hotel rooms and once went to a “jjimjilbang” bathhouse like a typical Korean mother and daughter, an intimate experience that Park says felt like a “rebirth.”

Park also developed a close connection with the woman’s son, who even changed his name to Park Joon Young, to share the “Young” syllable in line with Korean naming convention for siblings.

In 2012, Park asked the woman to take a DNA test. The request wasn’t based on suspicion but on Park’s unquenchable need for something “tangible” about her past: She hoped it might help find her father.

Park says that after learning that the woman was not her biological mother, she went through long hours of therapy.

As a licensed family therapist herself, Park has focused her practice in California on adoption and foster care issues. Her personal experience led her to redouble her efforts to understand the deeper problems around Korean adoptions. She says hitting the “lowest of lows” has informed her work in helping others cope with loss and trauma.

Park still wants to find her biological mother, but isn't sure where to begin since the information she had been given about her adoption turned out to be false. She wonders what happened to the real Park Joo Young, the biological daughter of the woman Park once thought of as her own mother. They no longer talk.

Park questions whether agencies should arrange reunions without mandating DNA tests when their records are not always reliable.

Eastern, the adoption agency, did not respond to requests for comment about Park’s case. Its president defended the agency’s overall practices, saying it was carrying out a government policy to find homes for “discarded children.”

Park says she received an email from an Eastern employee apologizing for the false reunion, but she’s upset that the agency has not taken ownership or responsibility for what happened to her.

I don’t know my real Korean name. I don’t know my real birthdate.

Rebecca Kimmel

Adopted in 1976 to the United States

Growing up, Rebecca Kimmel celebrated two milestone dates every year: Her birthday and January 21, the day she started her new life with her American family — dubbed “arrival day.”

“It was embarrassing for me as a kid ‘cause my parents were going to lug out all the photo albums and tell me the same stories again and again,” says Kimmel, who was adopted from South Korea as a baby in 1976.

The story Kimmel knew by heart was that the police found her abandoned in Gwangju with a slip of paper with her birthdate.

Kimmel carried a mental image of a woman leaving a child in a basket with her throughout her childhood and when she left for college and later became an artist. It never occurred to her to reconnect with her roots.

Kimmel says she became curious about her origin story in her early forties when she realized that the clock was ticking to find her birth family. She also wanted to resolve a lingering suspicion she had had since she was young: That the girl in the photo included in her adoption file did not look like her — and perhaps, was actually someone else. Her sense of urgency coincided with the growing international popularity of Korean pop culture, including makeup tutorials. Kimmel’s online forays eventually led her to Korean adoption groups.

"All of a sudden I find out that the Korean adoptee community is huge all over the world,” Kimmel says. “And I was like, ‘What?’ I've been missing out on all of this."

She attended her first adoptee gathering in San Francisco in October 2017 and found herself among hundreds of other Korean adoptees. That’s where she learned about a homeland tour that led to her return to South Korea for the first time in 33 years.

She also visited her adoption agency, Korea Social Service, but the meeting did not go well. Kimmel says she had a heated argument with a social worker, whose reluctance to provide her with full copies of her adoption records made Kimmel suspect the agency was withholding important information.

Kimmel says after the tense back-and-forth, the social worker reluctantly allowed her to take photos of her adoption file, which included another photo of the girl. Shot from a different angle, it solidified her vague suspicion that the girl was not her.

Kimmel later had these two photos from the adoption file cross-checked with early photos of herself in the United States by a dysmorphologist, a medical expert trained to identify birth defects in children, often from facial features. The dysmorphologist concluded that the girl from the adoption file photos was not likely to be Kimmel.

The discovery that everything she knew about her origins was false unmoored Kimmel. She joined multiple online forums where adoptees shared stories about their lives, birth searches and grievances.

“I’d opened this Pandora’s Box, and I didn’t feel like I could close it,” she says.

Kimmel discovered other Korean adoptees with switched identities who were also born in the 1970s and ‘80s, the peak years for South Korean adoptions.

Eventually, she found the adoption file of another girl whom she thought looked nearly identical to herself as a child. But the same dysmorphologist told her this girl probably was not her. Kimmel then became convinced she might have had a twin.

Not long after, she came across a post in a family search message board from a South Korean man who had given up twin baby daughters in the 1970s. Kimmel traveled to meet the man, but DNA tests eventually showed that this man was not her father.

Kimmel persuaded him to send his genetic samples to 23andMe, a U.S. commercial DNA testing company, which led to a reunion with his actual twin daughters — Dee Iraca and Becca Webster.

Although she was the catalyst for a reunion between people she’d never met, Kimmel remains stuck in her search for her own identity. Her agency, Korean Social Service, has not responded to requests for comment on her case.

“I don't know my real Korean name. I don't know my real birthdate,” Kimmel says. “I don't know whether or not I was a twin. ... I don't know who my birth parents are. I really know nothing.”

We do have a birth father who has been looking for us.

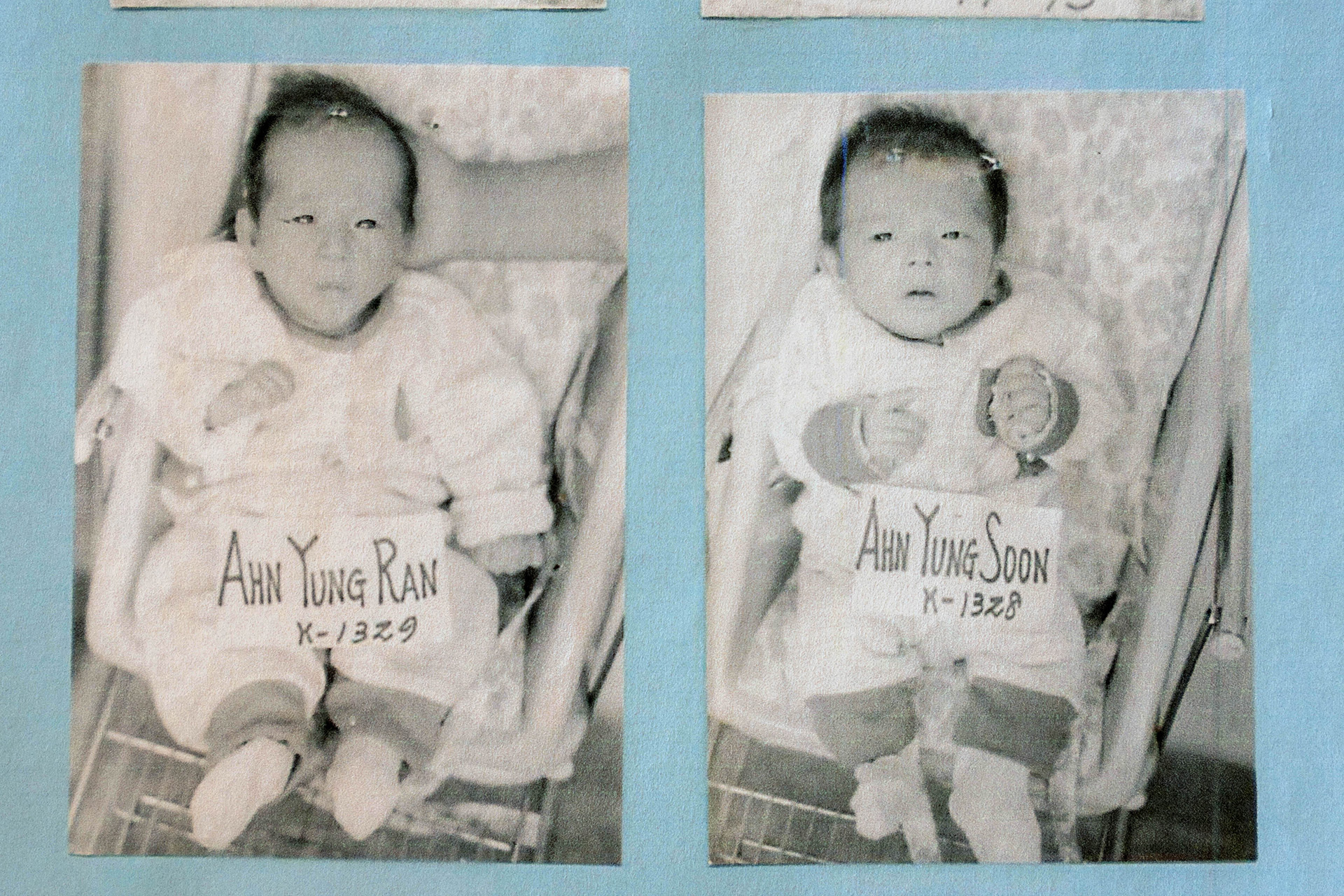

Dee Iraca & Becca Webster

Adopted in 1973 to the United States

Dee Iraca and Becca Webster, fraternal Korean twins who were adopted by the same family in the United States in 1973, thought there was nothing more they could find out about their past. Their adoption documents described them as babies found abandoned in front of a hospital.

They visited South Korea together in 2018 and met with their adoption agency, Holt Children’s Services, hoping for more details about their origin story. A social worker told them she had no more documents to give.

They said the social worker was sure they were found abandoned together. But Iraca and Webster were not convinced they were related, especially since they were so different. They decided to take a DNA test to find out if they were really biological sisters.

The DNA test confirmed that they were twins. Later, the ancestry website, 23andMe, pinged them with a message from another Korean adoptee, Rebecca Kimmel. She had met a man she had hoped was her father but he wasn’t. Despite that disappointment, she helped him submit his DNA to the 23andMe database.

There, Kimmel found his real daughters: Iraca and Webster.

Their father, Park Jong-kyun, says the story in their paperwork about how they were found is a lie. He says the family was very poor, and his wife had to undergo an emergency C-section that they couldn’t afford.

Park rushed out of the hospital, hoping to find relatives to borrow money from. When Park returned without success, he discovered that his wife had told a nurse she felt incapable of raising two more children because of poverty and her weakened health. He felt devastated. He says they reluctantly agreed to give their newborns up for adoption.

He remembers writing down the birthdates of the twins and putting those notes deep inside their blankets. He hoped he would find his daughters one day.

Park says he started actively searching for the twins when they were 10. For years, he sent agency workers boxes of tangerines, hoping to encourage them to help him search for his daughters. In fact, in 2018, Park had visited Holt in Seoul just two months before Iraca and Webster were there meeting a Holt social worker for help finding their birth family.

Park is frustrated that Holt missed an opportunity to reunite him with his daughters earlier. Now, at 84, he worries he doesn’t have much time left to spend with them.

Holt declined to comment on the case or any other individual adoptions. Agency officials have over the years denied any systemic wrongdoing and insisted they were finding homes for needy children.

The sisters are conflicted about their adoption journeys: They ended up with beautiful lives in America that they love. But that was all built on a system they say has been shaped by fabrication and deceit, affecting thousands, including their birth family. They resent that they never had the chance to meet their mother, who died at the age of 50.

I’m a person that wasn’t supposed to be sent.

Yooree Kim

Adopted in 1984 to France

It was two days before Christmas in 1983 when a worker from the orphanage Angel’s Home in Seoul delivered shocking news to Yooree Kim: Kim and her brother would be adopted to France.

Kim, then 11, says she was stunned and terrified. Angel’s Home was supposed to be a temporary refuge for the siblings, while their divorced mother tried to cobble together enough money to take care of them. It was common in South Korea for low-income parents to turn to orphanages to care for their children while they got back on their feet. Kim says her mother stayed in touch, sending letters and money over the two years she and her brother were there.

She demanded that an orphanage worker contact her family, but she says the worker refused.

When Kim’s mother came back for her children, they were already gone.

Kim, who arrived with her brother in the French town of Maurs in June 1984, says her adoptive father was abusive. She ran away at 17 and filed a complaint against her adoptive father. A judge dismissed the case, citing a lack of sufficient evidence. Her adoptive parents denied the abuse, as did her brother, she says. Her adoptive father passed away in 2022.

Kim says for years she harbored resentment and suspicion toward her biological parents, who claimed that they had never consented to the adoption. She returned to South Korea in 1994 and spoke to them.

Everything changed in 2022, when Kim went to a local ward office and requested her family registry. It showed she and her brother remained registered as their father’s children. That helped convince her that they’d never been voluntarily relinquished by their parents.

The discovery left her feeling that her “world collapsed.” Kim spent months bombarding Holt Children’s Services, the agency that handled her adoption, as well as the South Korean government and court offices with emails and phone calls, demanding explanations.

She says she only received a mix of evasions and non-answers.

“I’m a person that wasn’t supposed to be sent,” Kim said in an angry phone call she recorded with Holt’s former president, who’d signed her paperwork.

Kim is among hundreds of adoptees whose cases are being investigated by South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission for possible human rights violations. She hopes to use the findings to take legal action in the future. She has also requested that French authorities investigate her adoption as a case of kidnapping.

The cases highlighted here represent just some of the issues that children of the South Korean adoption boom have encountered, as they try to find their roots as adults.

For some adoptees, the search for answers has led to heartbreaking discoveries that their parents never abandoned them. Some have found that they are not biologically related to the people listed in their adoption files. Others have been hindered by a birth search process they see as burdensome and fear that time is running out to find their birth parents. Many wonder what their lives might have been like if they’d never left Korea.

Explore more stories from South Korean adoptees

Michaela Dietz

1983United States

Mia Lee Sørensen

1988Denmark

Robert Calabretta

1986United States

Anja Pedersen

1976Denmark

Alice Stephens

1968United States

Tona Richter Hansen

1977Denmark

Kenneth Barthel

1979United States

Maria Leister

1979United States

Nicole Motta

1985United States

Credits

FRONTLINE

Lead Designer: Dan Nolan • Senior Developer: Anthony DeLorenzo • Editors: Priyanka Boghani, Patrice Taddonio • Senior Producer: Nina Chaudry • Additional Writing and Reporting: Inci Sayki • Additional Research: Kristina Abovyan • Video Editing and Captioning: Miles Alvord, Tessa Maguire • Documentary Director: Lora Moftah • Director of Photography: Victor Tadashi Suarez • Editorial Review: Amy Rubin • Archival Producer: Coral C. Salomón Bartolomei • Special Counsel: Dale Cohen • Senior Editor: Lauren Ezell Kinlaw • Managing Editor: Andrew Metz • Executive Producer & Editor in Chief: Raney Aronson-Rath

Associated Press

Written and Reported by: Kim Tong-hyung, Claire Galofaro • Editors: Jeannie Ohm, Mary Rajkumar • Photography: Nat Castaneda, David Goldman, Jae C. Hong, Jacquelyn Martin, Lindsey Wasson, Ahn Young-joon • Video: David Goldman