Oh my God!

There they are.

Right there!

Be careful.

Don't step on a Toad.

How do I?

You can just open it and let them jump out.

Or you can just grab them and try.

Okay.

It's up to you.

Look!

Yummy!

Tempting?

Are you tempted by these delicious crickets?

Oh God, I'm so scared.

Why am I so scared?

Oh God!

Freaked out!

Bre brave, be brave!

Come on!

Got it, got it, got it, got it.

Got her, got her, got her, got her.

Sorry to bother you.

I know.

I know.

I know.

I'm sorry.

I'm sorry.

It's uncomfortable for me too.

Not good.

So, this is Martha.

She's a cane toad.

Martha here is cannibalistic, at least sometimes.

She's extremely poisonous.

Please do not put her in your mouth.

And she's responsible for the threatening of tens of species, the invasion of and destruction of habitats in 15 different countries at least.

And is representative of arguably one of the worst failures in history of ecology.

What you have to say to yourself?

Huh?

That's why I thought.

But before we dive into the many crimes of our good friend Rhinella marina, we have to talk about Sugar.

Like many of the world’s problems, the cane toad issue starts with imperialism.

The countries of Western Europe built their empires in large part on crops, farmed in their colonies via enslaved labor.

By the 1700s, Britain had hopped on the sugar cane train too, growing it in places like Barbados, Jamaica and eventually Australia.

Over the course of the next century, Sugar made Britain massive amounts of money.

And by the way, it's still grown in most of these places.

In fact, about 80% of the sugar produced today still comes from the sugar cane plant.

I put too much sugar in that...

But this crop, and therefore the money was vulnerable to pests, insects and small mammals that would eat the sugar cane and decrease the yield.

The solution was toads?

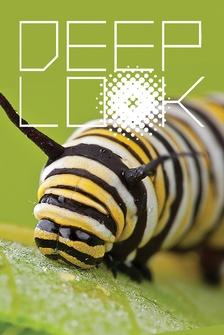

See, the cane toad is native to Central and South America, where they've evolved to be just one piece of a balanced ecosystem.

But these toads will eat basically anything.

So, folks decided to throw some toads at the pests threatening their cash crop.

Cane toads were first introduced as pest control in the mid 1800s when they were brought to Barbados from what is now Guyana.

And from there they were brought either on purpose or by accident to over 130 different countries and islands.

Despite very little evidence that the toads actually worked.

To make a long story short, the cane toad became trendy.

It was a fashionable answer to the sugar cane industry's problems, and by the 1930s, Australia's sugar cane business had exploded, but so had the cane beetle population.

These bugs are native to Australia and they love eating the leaves, stalks and roots of the sugar cane plant.

So, with absolutely no investigations into how they would work in Australia, specifically in 1935, Australian scientists decided to import a couple hundred cane toads to hopefully hunt and eat the cane beetles.

and what followed can only be described as a complete and utter total abject failure.

Cos, see The cane beetle likes to live further up on the sugar cane plant.

And because of those stubby little legs, the cane toad couldn't get up there to eat the beetle.

The toads also weren't digging down into the dirt where the grubs were feasting on the roots of the crops.

So, the toads never really came across these insects at pretty much any point in their life cycle.

And what's even worse is that they may have actually increased the cane beetle population.

Yeah, they may have eaten a few, but they also ate and or poisoned a lot of the predators that were already naturally eating the cane beetles.

So overall, a net negative.

This is my friend Robert.

He has a lot more experience than I do catching and filming reptiles and amphibians.

So, he's going to be in front of the camera for a while and I will be the one holding it.

And while we didn't make it all the way to Australia, we are in what could be considered the Australia of America, which is Florida.

In any ecosystem, there's generally three broad categories of organisms.

There's the native species, organisms that can be naturally found in an environment and have evolved to fill a certain role within it.

Oh that’s it, it’s tired.

Then there's a second category, the non-native species, that nonetheless aren't really causing any major issues.

An example of that would be this palm tree.

It’s not from Florida.

It's not native, but it's not out on some sort of killing spree, decimating the native species.

It's just kind of sitting here in this yard looking relatively stately, you might say.

Under that umbrella of non-native, there's a third category.

The non-native invasive species.

Now, these are the real troublemakers.

They’re not really malicious, but they're really successful at what they do.

These are organisms that have been introduced to an environment and are causing harm and having a negative impact on the native flora and fauna.

An example of this is the common house cat, which actually ranks in the world's top 100 worst invasive organisms responsible for the extinction of at least 33 species of modern birds, mammals and reptiles.

Another example of an invasive species.

Our friend, the cane toad.

Because cane toads aren't just a problem in Australia.

They've also made it all the way to Florida.

I grew up in South Florida.

I was born in North Miami Beach, so I'm a native Floridian here and I have always grown up playing with bugs and fishing and being outdoors, and that's what I love.

So, as a child I was always into reptiles.

I was probably one of the first women in the industry.

So, I was collecting and looking at our native species, and I kept seeing the invasive species growing, and these toads were like becoming more common than anything else.

And I always had this idea like, there's got to be something we can do to control the toads, and you know, that’s when I decided to create Toad Busters.

Yeah, there's one right there.

Okay, so we like to look around the bases of the trees because toads are territorial, so they generally like to be one per tree.

So, here's a perfect example.

This one just popped out of the leaf litter.

All right.

So we're going to go ahead and grab this.

Right.

But look at how big this one is.

Now, because I grabbed her.

I want you to look and see how much toxins are coming out of those glands.

See, cane toads secrete this sticky white substance called Bufotoxin.

I was working as a veterinary technician and pet emergency people would bring their dogs in and the dogs would have either died or been sick from it.

And I realized that there was nothing out there to help them.

Actually, there is not really an antivenom for it or an antitoxin.

The dog doesn’t have to actually bite the toad, he can leak it.

Just put his nose on it, and then leak it off his nose and that immediately, specially a dog this small you’ll see a reaction right away.

He is going to start salivating, his gums are going to get red, his eyes are going to dilate.

They’re going to start vomiting, shaking their head, and then, their body temperature starts to go up, and then, they’re going to a seizure, and it’s super scary!

These glands are very full, so if I actually squeeze it, it would squirt out all the way.

Probably about four or five feet from here.

No freaking way!

Yeah... Now, so it is kind of, like, cheesy, creamy.

So it sticks.

You see, It's like.

It's not like, coming off really easy.

So that's what happens when the dog gets it in the mouth.

It sticks in the mouth.

And it's not just our household pets that are affected.

Cane toads are so problematic not only because they can make themselves at home so easily in so many environments, but because anything that eats them can be affected by their toxin.

And ecosystems are complex webs of energy.

If a predator is eliminated by a cane toad, then the thing that the predator eats can multiply and suddenly the whole ecosystem gets out of balance.

You know, one of the big problems we have here is all this new development.

We've created a paradise for them.

We have these wonderful ponds and lakes that we create that are fairly sterile, very easy for them to get down to breed.

and the females all come down, and they have a big party here.

They lay hundreds of thousands of eggs.

When they come out, it's a mass exodus and you can't like get out of your house without stepping on them.

The homes, have lots of mulch and they bury down into the mulch during the day because they're nocturnal.

and we've got all these beautiful outdoor lights which I call them McDonald's or Taco Bell, Burger King, because they wait by the light and the bug comes down, hits the light, knocks itself semi out, hits the ground, toad eats it.

And that's pretty much what they do all night.

They’ll actually congregate here over going to the wild.

Even when it's dry, they know to go by the air conditioners where the runoff is so they can still get water.

So, anything that can create a burrow for them, they'll pretty much live in.

And not only is the human made environment just super cushy for them here, but cane toads have also evolved several traits that make them absolute tanks when it comes to succeeding pretty much anywhere.

They pretty much eat anything that moves, even if it's their same size, they'll actually eat each other.

We’re definitely are making a difference by going out and collecting them and removing them.

So, once we remove these guys out of here, we see the native stuff coming back in the southern toads, the spayed for toads, and that's really helping the environment as well as helping people's pets.

So, on our busy nights, like if we're doing a large community or golf course community, we can bring in between 6 to 800 toads in the evening, just one person.

We started ten years ago and at the beginning there was what we call the season.

We would reach a point starting in December through March where the numbers would drop.

We wouldn't really collect much.

But since then it's probably been seven years now.

We noticed that we're not getting those cold snaps that lasts several weeks to drop the pond water and lower the amount of insects that we have.

And now where we were catching maybe 60 during that time, we're still catching thousands.

And that's the difference that we're seeing is this I'm assuming it's global warming.

We're also watching where the toads are coming from.

they're moving up towards Orlando.

We started Vero to the Keys.

Now I'm getting calls from Orlando.

We got a call from Jacksonville.

We confirmed the toads were there.

So, that means that the toads are moving up the coasts where they can access water.

So during the cold snaps, they're not getting cold enough to stop them from moving.

And I imagine slowly over time, they're going to develop ability to handle the cold and continue up through the state.

Is huge!

Yeah.

This is a big girl.

This is she's full of eggs right now.

That's why we got... See the belly on her?

Oh wow!

Yeah.

Super important to get her then, yeah?

Yep.

So, removing her is a big, you know, a big win.

Decreasing the number of cane toads through individual collection is an incredibly important piece of the puzzle to help native species keep a foothold in the ecosystem.

But there's only so much, Janine, to go around.

And in Australia, some studies have recorded 40% fewer native species at sites occupied by cane toads, with huge declines in native mammal and reptile species, including the already vulnerable quoll.

In less than 100 years, those original few hundred toads have multiplied to over 2 billion toads, and they've made it almost to the opposite coast of Australia.

So, in search of more answers to problematic species like cane toads, we said goodbye to sunny Florida and to Robert and hello to cold gray England, where we spoke to a researcher who's working on some pretty high tech methods to help us understand and tackle the problem of invasive species around the world by looking at the bigger picture.

The situation we are faced with right now is sometimes they are environments where nothing strives except the invasive.

There's also some environment where they have been completely taken over by invasive.

Think about gray squirrels in the UK.

So, the idea that we could remove it altogether, is just not feasible.

And then on top of that, you have species moving with climate change, which one can you actually control and how do we deal with that situation in a way that is sustainable and realistic and in a way that enable nature to either reorganize itself or deal with new components within its ecosystem in a way that still makes it a functioning ecosystem.

Okay.

So, like is there a version of this ecosystem that includes things that may not be native to this space, but the ecosystem is still functional and as we are choosing to define it healthy, and so we can bring it back to a healthy state, which may not necessarily be a native or natural state.

Not only a healthy but a resilience.

So, something that can cope with the changes ahead.

So if you think about those ecosystem, how they have changed and how new species are arriving all the time, you kind of need to know what's coming, what's there, what was there before, what's there now, and how is the ecosystem responding to that?

So what I do is that I try to use information collected by satellite to help manage wildlife in places where it's difficult to go or it's very big or we don't have much information.

The beauty shot here.

The idea was that someone in the team would prepare a hat for someone else in another team, based on their research.

I love it!

So that's the hat they did to me.

Which is why I...

So good!

No, I’ll never gonna do that.

Thank you!

Now there are different type of satellite.

Some of them, you can imagine them like big cameras taking shots of the earth.

And what they do is that they do that all the time for decades, which means that you can look backwards in time, and see how Earth was 40 years, 30 years, 20 years ago.

So, that allows you to detect how those species change in distribution.

How those ecosystem in communities change in distribution, but also how they are reacting to various pressures such as climate change.

So you can have indirectly some information about the population dynamics of those species, So you can measure the invasive animals impact on the ecosystem.

Yes, if it has a clear one, then you can.

So again, it tells you how quickly it's spreading, what kind of environment it's able to invade, whether or not it's changing the functioning of an ecosystem, which again, will be important to inform conservation and wildlife management.

So, satellite is not the only type of technology that allows you to track nature because there's a bunch of technology that have been designed for getting information about nature remotely and that's what's called Remote Sensing.

So, Remote Sensing includes satellite, which we just talk about, but it also includes drones.

It includes camera traps.

Oh they're like the ones where an animal goes... That’s right!

It works night and day.

And then whenever something goes, it's triggers it to take a picture and then you can see what it is...

I love this little camouflage outfit.

These are really good for animals that don’t like to be seen.

The sneaking ones!

and...

Your phone!

I can remote sense?

You can remote sense.

You go around, you see an animal, you take a picture, you upload it on something like iNaturalist like an app or even on social media.

And what you're actually doing is remote sensing.

And if you upload it in the right app, you're actually giving me data.

no.

Oh no way!

Yeah!

It's like the world can source data.

And it does it super well when it talks to things such as invasive or species that are moving with climate change, People are extremely good at picking that up.

And if they enter the information you will have a community of expert that also check it out.

And then when everybody agrees on what it is, it goes into a big database shared with all scientists.

And then we can use that to try to see what's going on in terms of movement of species around the globe.

Oh that’s so cool!

I love the idea that, like all of us around the world, can help you know, curate that knowledge about how our world is changing.

We really do need them.

And when you think about all the animals, all the species, all the plants, it’s really, really difficult to keep a track on all of this.

Of course!

So, everyone is needed.

And yes, you need to be seeing things differently because science is not about regurgitating what you know, it's about finding new things.

Yeah.

So which means thinking about outside the box, trying things, getting things wrong.

And sometimes when you're lucky, getting it maybe right.

So, while invasive species like cane toads may be here to stay.

All kinds of really cool science, including the kind that you can contribute to with your smartphone can hopefully help us better understand their spread and their impact.

So, we can decide how best to tackle them as we move into an unpredictable future, and hey, happy Earth Month.

PBS is dropping new content all month long about this amazing planet that we all live on.

And I especially I've been enjoying the series Stop Saving the Planet, which argues that environmentalist needs to change its approach.

If we want Earth to not become a fascinating fail You can check out that series and all of the other Earth Month content on PBS Terra’s YouTube channel.