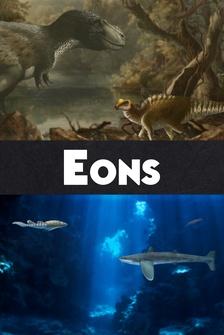

(birds squawking) (light music) (water moving) - This is one of the most important forest ecosystems on earth.

Okay, not a forest like you were expecting, right?

But trust me, this forest ecosystem is every bit as beautiful and epic as a forest on land, only instead of being made of trees, this one is made of giant towering strands of kelp.

(light music continues) But this epic forest is in danger of disappearing.

Luckily, an unlikely team of marine mammal researchers, underwater ecologists and algae farmers is fighting to bring this forest back from the brink.

Like every forest, this one has predators to help keep it in balance, and one of those predators is really stinking cute.

I mean, have you ever seen anything that adorable in your life?

(light music continues) Kelp forests are the foundation of this marine ecosystem.

Without them, this environment would not exist as we know it.

They support over 800 species and provide crucial habitat and food.

Kelp forests like this one can be found in cold water regions all over the world.

Now, you might be tempted to call kelp a plant, but don't.

Kelp is a type of macroalgae, which means it doesn't have roots, stems, or leaves like plants.

Kelp forests have been a part of these coastlines for more than 30 million years.

One of the dominant species of kelp here in California is bull kelp.

It's the trees of this underwater forest, and these kelp forests thrive in part because of animals like sea otters.

They're part of a complex love/lunch triangle between predators like otters, kelp, and underwater plant eaters like sea urchins.

Here's how it all works.

Urchins eat kelp, which is fine, so long as someone eats the urchins.

Someone like our cute and hungry friend here who can eat up to 15 pounds of seafood a day.

An otter's appetite protects the kelp forest from being overgrazed.

The kelp keeps the urchin happy and fed.

The urchin keep the otter healthy and fed, and the otter eating the urchin keeps the kelp from being overgrazed.

Scientists call this type of carefully balanced relationship between different species a trophic cascade.

(gentle music) But here's the thing.

This carefully balanced trophic cascade has fallen apart in Northern California.

Otters are fighting for their lives here.

European settlers decimated the otter population in the mid 1700s and early 1800s as part of the fur trade, but researchers are trying to bring them back one otter at a time.

(gentle music continues) (birds squawking) - [Sandrine] My name is Sandrine Hazan and I rescue and rehabilitate sea otters.

- You get to take care and rehabilitate and release the cutest animal on earth into the wild?

- I do that.

Yes, I have that badge.

This is a receiver that's used to pick up a signal that a released otter would have, so they are implanted with a transmitter that has a specific frequency, and we can pick that up with this receiver.

We recently released Otter 956 just out here in the kelp bed, and so we have been tracking her on a daily basis.

- Let's cut this joyous otter release footage.

(soft music) Why do all this work?

Why do all this trouble to to track, you know, one otter?

- Well, it's really part of the bigger picture of helping to bring these otters back to their historic habitat.

They are keystone species and they really do so much for these kelp forests, keeping them healthy and keeping them balanced.

- [Joe] After the otter population disappeared, another predator stepped up, sea stars, particularly the Sunflower Sea star, with its dinner plate sized body and up to 24 limbs.

They began to dine on urchins becoming formidable urchin hunters themselves, but then a series of events turned hundreds of miles of California coastline, a spiky purple.

Suddenly a mysterious marine disease nearly wiped out sea star populations, and then a roving ball of warm ocean water known as the blob rolled through the region causing sea temperatures to rise by two to three degrees Celsius.

The trophic cascade fell out of balance.

The sea stars disappeared, the urchins went wild, and 96% of the kelp canopy along Northern California's coastline has disappeared in the past decade.

A region spanning 350 kilometers of the coast.

(soft music) (waves lapping) (bird squawking) - I think we're ready to go.

Got my camera.

Yeah, let's do it.

(soft music continues) - [Joe] One of the last remaining strongholds of bull kelp is here in Mendocino County in Northern California.

- We're kind of left in a situation where there is no natural predator in the sea right now.

And so what I work on specifically is trying to find ways where human can temporarily mitigate and help fill that role until we're able to have some level of apex predator back in the system.

(soft music continues) This is our coral reef.

This is our great barrier reef for Californians.

It's kelp forests.

Kelp and the ecosystems they create are why we have any fish in the ocean.

They create food, habitat and shelter for hundreds, if not thousands of organisms, including human.

- [Joe To understand the extent of the loss, scientists like Tristan have turned to aerial imagery and high resolution mapping, looking at kelp from both below the water and from above.

- So what you're looking at right there is the dark green patches, and this was just this past fall, and that's where, that's the only area where we saw kelp.

And so what we're focused on now is looking at where kelp has been persistent and it's survived, so then we can really focus our kelp recovery efforts in a way that's meaningful, impactful, and then also leveraging persistent kelp refugia.

- [Joe] One of those recovery efforts involved roping in aquaculture researcher, Andrew Kim and his team to plant lab grown kelp in the waters of Northern California.

- [Andrew Kim] We've developed these methods for being able to grow kelps year round.

Being able to put kelps out that are already ahead of the curve and giving them really just a headstart in the environment, I think is a big breakthrough because for an annual species, like the bull kelp, it extends the potential window for them to be reproductive and to put spores into the environment.

- [Joe] Bull kelp like this regenerates every year growing from a microscopic spore to a huge structure dozens of meters tall.

(soft music) This kelp can grow up to 60 centimeters per day, making it one of the fastest growing organisms in the ocean.

After three years of trial and error, Andrew and his team are seeing success with new ways of planting their lab grown kelp designed to protect young kelp from predators and harsh conditions.

- Kind of like you would plant a raised garden bed if you had animals like running through your garden, you could put your seaweed in, in a raised bed and keep it out of the hungry reaches of the urchins.

About a month ago, we put out kelps that were about six to 10 inches, and we came back and we surveyed these modules, and in the last month, they've grown several feet and they're already attracting lots of fish.

Every time we put kelp out, we're putting a piece of hope out.

You know the hope that it'll create home for some little fish.

It's a big ocean.

We just need to keep working and chipping away.

We're all in this together and we need to keep trying.

(soft music continues) - Back in the rich marine waters of Monterey, Sandrine is working hard to support otters as the cute, hungry predators fight to retake their place as the keystone species of this ecosystem.

Do we have ears on 956 right now?

- We do, yep.

This is her signal and she is somewhere nearby and based on this signal, she is resting.

- Do you think in your lifetime that otters in the kelp forest will be restored north of here?

- I hope so.

The sea otters are trying really hard to expand their range, and we are doing everything we can to support conservation efforts to help them restore back to their range.

- It sounds like you take it day by day, otter by otter around here.

- Yes, very, very much so.

- 956, wherever you are, I hope that you're getting lots of good urchin snacks.

(gentle music) The kelp forest reminds us of the wonder that's out there in nature, sometimes literally right beneath the surface.

It's also precious and so fragile.

We just have to take it one breath at a time.

(gentle music continues)